HUFF FAMILY HISTORY

compiled by Kent Alan Huff, March 22, 2010

compiled by Kent Alan Huff, March 22, 2010

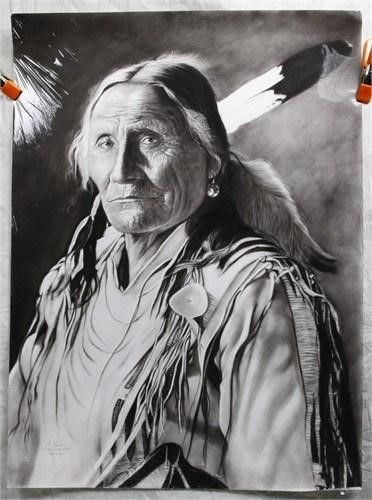

Opechancanough. A Powhatan chief, born about 1545, died in 1644.

He captured Capt. John Smith shortly after the arrival of the latter in Virginia, and took him to his brother, the head-chief Powhatan. Some time after his release, Smith, in order to change the temper of the Indians, who jeered at the starving Englishmen and refused to sell them food, went with a band of his men to Opechancanough's camp under pretense of buying corn, seized the chief by the hair, and at the point of a pistol marched him off a prisoner. The Pamunkey brought boat-loads of provisions to ransom their chief, who thereafter entertained more respect and deeper hatred for the English. While Powhatan lived Opechancanough was held in restraint, but after his brother's death in 1618 he became the

dominant leader of the nation, although his other brother, Opitchapan, was the nominal headchief.

He plotted the destruction of the colony so secretly that only one Indian, the Christian Chanco, revealed the conspiracy, but too late to save the people of Jamestown, who at a sudden signal were massacred, Mar. 22, 1622, by the natives deemed to be entirely friendly.

In the period of intermittent hostilities that followed, duplicity and treachery marked the actions of both whites and Indians. In the last year of his life, Opechancanough, taking advantage of the dissensions of the English, planned their extermination. The aged chief was borne into battle on a litter when the Powhatan, on Apr. 18, 1644, fell upon the settlements and massacred 300 persons, then as suddenly desisted and fled far from the colony, frightened perhaps by some omen. Opechancanough was taken prisoner to Jamestown, where one of his guards treacherously shot him, inflicting a wound of which he subsequently died.

Story copied from: http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/DODSON/2006-

- Chief Eagle Plume’s Daughter, Jane Eagle Plume (1584-1655) , reportedly married John Dod(son), who emigrated from England on the Susan Constant, arriving in Jamestown in 1607.

- Some accounts, however, say he married a young woman named Jane Dier who was also from England, and the ship’s records say he came over with his wife, Jane, aged 40, so his marrying an Indian Chief’s daughter may be just legend:

The Dodsons of Virginia and West Virginia can trace their origins to John Dods, who departed London aboard the "Susan Constant" on December 19, 1606 along with Captain John Smith. The "Susan Constant," along with her sister ships, the Discovery and the Godspeed, took the long route around the Canary Islands arriving on the Virginia coast on May 6, 1607. The ships were driven inland by a storm and they took refuge in the area that is now known as Hampton Roads, Virginia. They then sailed up the James River landing at Jamestown. John Dods was listed as a "labouror" on the passenger list for original 105 settlers of Jamestown. He was also a soldier in the expeditions against the Indians. John was born in England in 1588 and was 18 years old when he arrived at Jamestown. He married Jane Dier, one of the 57 women sent to Jamestown from England aboard the ships Marmaduke, Warwick, and Tiger in 1621, as brides for the single males at Jamestown. Jane was the youngest of the women {typographical errors removed} and was said to be 15 or 16 when she arrived in VA. (The source of the information concerning Jane Dier is the William & Mary Quarterly, January 1991. Article by David R. Ransome, "Wives for Virginia, 1621."

John and Jane survived the hardships of winter, starvation and the Indian massacre that took the lives of the majority of the original Jamestown settlers and went on to prosper as a member of the Land of Neck community with the status of "Original Settlers". The census taken by the Virginia Company of London in the years 1624 and 1625 list John Dods and his wife Jane as living in the Land Of Neck village along with over forty other individuals. (The Historical Journal, 43, 2 (2000) @2000 Cambridge University Press. Village Tensions In Early Virginia: Sex, Land, and Status At the Neck Of Land In The 1620s. David R. Ransome.

It is believed that John Dodds and Jane had two sons and in naming his sons John probably used the popular practice of the day, known as "patronymics". Patronymics describes the act of creating a new name for a male members of the family by adding the suffix "son" to the fathers name. If this is the case the name Dodson stood for the "Son" of Dod.) "MARSH AND RELATED FAMILIES"

Chief Eagle Plume is listed with LDS records. Chief Eagle Plume was under the chiefdom of Powhatan and was not of the Colorado tribe in the state of Colorado. There are some Eagle Plumes in the state of Colorado but they are not of the group under Powhatan. When the Spaniards first arrived at Virginia, they met red men (Indian) and they named them the Colorado for in Spanish the term Colorado means 'red or reddish'. (The American Heritage Larousse-Spanish Dictionary)I hope this information will help in your research. There was an article in a Genealogy Magazine regarding the James River and the founding of Jamestown and the Powhatan Indians were the ones that the settlers had so many wars with. They finally called peace in 1611 with the settlers.

- John Dod had a son named Jesse Dodson (1623-1716) – the last name Dodson came from forming a patronymic, “Dod”+Son, the Son of Dod.

- Jesse Dodson had a son named Charles Dodson (1649-1703)

- Charles Dodson Sr. had a son named Charles Dodson Jr. (1675-1715)

- Charles Dodson Jr. had a son named Thomas Dodson (1681-1740)

- Thomas Dodson Sr. had a son named Thomas Dodson Jr. (1707-1783)

- Thomas Dodson Jr. had a son named William Dodson (1738-1832)

- William Dodson had a son named Simon Dotson (1761-1849) (the last name got changed here to Dotson)

- Simon Dotson had a daughter named Mary Polly Dotson (1817-1877)

- Mary Polly Dotson married Charles Huff (1812-1862)

- Charles Huff’s son was John Huff (1845-1900)

- John Huff’s son was Worley Huff (1882-1940)

- Worley Huff’s son was Arnold Huff (1906-1950)

- Arnold Huff’s son is Gary Kenneth Huff (1946-)

Gary Kenneth’s son is me, Kent Alan Huff (1965-)

Tina Miller, who claims to be a great++++++++ granddaughter of Chief Eagle Plume, posted this message, however, which leads some credence to the story, and also describes a relationship to Pocahontas:

Coming to Virginia in 1607 on the Susan Constant John Dods was one of the original settlers of Jamestowne: While there is no specific "official" list of those who came to Jamestowne there are several respected lists mainly stemming from Capt John Smiths writings. On the Internet I quickly found two websites with the same list. One is at the Virtual Jamestowne website at http://www.virtualjamestown.org/census2a.htmland another at Jamestowne Rediscovery website at http://www.apva.org/history/orig.html

On both websites John Dods is listed as a laborer. He was also sometimes listed as a soldier as well.

In his book The Complete Book of Emmigrants 1607-1676 part of which is posted online athttp://www.runningdeerslonghouse.com/webdoc38.htm

Peter Coldham lists John Dods as of 1626 owning 50 acres in Charles Cittie and another 150 acres in the Territory of Tappahanna. Coldham also lists John Dods and Mrs. Dods as living at At the Neck of Land February 1624 as named on the List of the names of the living in Virginia and of those who have died since April 1623. This means they survived the Indian attack of 1623 that wiped out much of the Jamestowne Colony. This list is an old list, too. It is just that is published on the Internet now. The list was created as a census of those who survived the Indian attack in 1623. This list also shows John Dods survived the Starving time of 1609-1610 when much of the early colony died of starvation and disease. It also shows he evidently married and both he and his wife survived the Indian attack of 1623 that wiped out much of the colony. The lists name John Dods' wife as Jane which gives credence as to the given name of his wife. While it is possible Jane was a Indian maiden/princess as the tradition likes to say. Marriage between Englishmen and Native Americans were not the norm. John Dods & Jane Eagle Plume named there sons Jesse, William, & Benjamin Dodson. John Dods married before the first Brides ship ever arrived at Jamestown; the brides ships did not arrive until John Dods sons were of age to marry. William & Benjamin were married to English Women and Jesse also married from the Powhatan Tribe.

It is to believe that not only John Smith and John Dods (Dodson) were cousins, but

Pocahontas and Jane were cousins as well. It is also said that Pocahontas and Jane's Fathers were brothers. There were both Chiefs. Chief Eagle Plume was under the rule of the Powhatan Confederation. He was one of the great chiefs of the Powhatan tribe brother to Werowocomoco.

Pocahontas was the daughter of the Algonquian chief Powhatan.

She and

her tribe lived in the wilds of Virginia at the time of the

founding of the first permanent European colony,

Jamestown. She was by all accounts remarkable and important to

relations between the English settlers and the Native tribe.

Poor relations with the Algonquians and dissent within

the colony prompted

Captain John Smith, one of the leaders of the colony, to go

exploring in search of the chief along the James River. His

experiences there form the basis of the legend of Pocahontas. He

searched for Powhatan, the chief of the Algonquians, in 1607, along

the Chickahominy River. A hunting party attacked the men he left at

the boats and captured him. Smith amazed them with his compass,

earning an audience with Powhatan at Werowocomoco, 12 miles from

Jamestown. Smith later wrote that he was taken to Powhatan and

sentenced to death. In his Generall Historie of Virginia published

in 1624, Smith described his controversial rescue by the chief's

daughter Pocahontas. Pocahontas was a nickname meaning "little

playful girl, or favorite." Her real name was Matoaka.

"Having feasted him . . . A long consultation was held, but the

conclusion was, two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then

as many as could lay hands on him, dragged him to them, and thereon

laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beate out his

braines, Pocahontas the Kings dearest daughter, when no intreaty

could prevaile, got his head in her armes, and laid her owne upon

his to save him from death: whereat the Emperour [Powhatan] was

contented he should live to make him hatchets, and her bells,

beads, and copper . . ."

His claim that Pocahontas saved him when the others tried to beat

his brains out with a rock is probably either invented or

romanticized. It is possible that the Algonquians enacted an

"execution and salvation" ritual to cement the agreement. This

would not be unusual, and it is possible that Pocahontas, who was a

young girl, participated in it.

[Pocahontas] not only for feature, countenance, and

proportion, much exceedeth any of the rest of his

[Powhatan's] people: but for wit and spirit, the only

Nonpariel of his Country.

John Smith, True Relations Later, in 1613, Pocahontas became a

valuable hostage to the English. Sir Thomas Dale had her instructed

her in Christianity, and here she met a tobacco planter named John

Rolfe. She was given some degree of freedom within the settlement.

After almost a year of captivity, Dale finally returned her to her

father. He brought 150 armed men into Powhatan’s territory to get

the entire ransom from the chief. The Algonquians attacked the

party, and in retaliation, the Englishmen destroyed villages,

burning many houses, and killing several men. Pocahontas went

ashore where she met with two of her brothers. She told them that

she had been treated well and that she wanted to marry John Rolfe

to ensure peace for her people. The bargain was made. The

prospective bridegroom was not enthusiastic. He would not consider

marriage to Pocahontas until she converted to Christianity and

even then had grave doubts. However, in some personal turmoil about

his relationship with her, he agreed to the marriage. He wrote a

long letter to Governor Dale asking for permission to marry

her.

"It is Pocahontas," he wrote, "to whom my hearty and best thoughts

are, and have been a long time so entangled, and enthralled in so

intricate a labyrinth that I (could not) unwind myself thereout."

He married her "for the good of the plantation, the honor of our

country, for the glory of God, for mine own salvation."

Pocahontas accepted baptism, took the Christian name of Rebecca,

and married Rolfe on April 5, 1614. The marriage helped to keep the

peace between the Algonquians and the settlers. In the spring of

1616, Sir Thomas Dale sailed back to London to secure more funding

from the Virginia Company. He took a dozen Algonquin men.

Pocahontas also made the voyage with her husband and their young

son, Thomas. The arrival of Pocahontas in London was well

publicized and she became a celebrity. She was presented to King

James I, the royal family, and London society. Here she met again

Captain John Smith, whom she had not seen for eight years.

According to Smith's rather melodramatic account of their final

meeting, when they met she was at first too overcome with emotion

to speak. After composing herself, they spoke about Jamestown and

their experiences there. At one point she addressed him as

"father," and when he objected, she said: "Were you not afraid to

come into my father's Countrie, and caused feare in him and all of

his people and feare you here I should call you father: I tell you

I will, and you shall call mee childe, and so I will be for ever

and ever your Countrieman." (John Smith, Captain John Smith's

Generall Historie of Virginia)

Seven months later, Rolfe set sail for Virginia with his wife and

child. Pocahontas became seriously ill (pneumonia or tuberculosis)

after they sailed. They took her ashore, and as she lay dying, she

consoled Rolfe, with "...all must die. 'Tis enough that the child

liveth." She died at the age of 22, and was buried in Gravesend,

England far from her home.

kent@huff-family.info

Copyright 2015 © Kent Huff

All Rights Reserved.